Promising to see a bunch of jobs being advertised, pushing on now Stadium (almost) is ready.

Tottenham Hotspur FC Jobs (22) - Football Vacancies

Tottenham Hotspur FC Jobs (22) - Football Vacancies

The Fighting Cock is a forum for fans of Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. Here you can discuss Spurs latest matches, our squad, tactics and any transfer news surrounding the club. Registration gives you access to all our forums (including 'Off Topic' discussion) and removes most of the adverts (you can remove them all via an account upgrade). You're here now, you might as well...

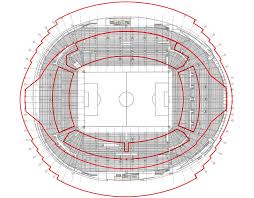

I would imagine it has to do with it being designed as a true multipurpose venue, but the enthusiasts over at SSC would know better.Was taking the piss out of a West Ham fan just now by reminiscing about this photo of their place over ours and I noticed something about the plans for the new stadium.

Every corner has a doorway or opening. You don't see that with many stadiums, even new builds. Usually there's one opening, two max yet we've got walkways or ways in/out in every corner. The North East corner is for the emergency services and the NFL but does anyone have any idea what the others are, especially the ones where the East & West stands meet the South Stand?

If someone's put off by the length....

I can't read it as I've reached my article limit.....

Tottenham Hotspur’s new stadium should be a source of pride for all of football

You missed one out-I can't wait for the first opposition fan reviews.

'It was too noisy'

'There was too much choice of food'

The head on my beer was too small'

'It's too big'

'it lacks the 'roughness' of xx stadium'

The excuses will be hilarious

Blatant "look at me with my proper newspaper subscription i.e. I can read"...FOOTBALL | HENRY WINTER

march 26 2019, 12:01am, the times

Tottenham Hotspur’s new stadium should be a source of pride for all of football

henry winter, chief football writer

The fabled American sporting arena, Candlestick Park, opened on April 12, 1960 in the Bayview-Hunters Point district of San Francisco, a community needing love and investment after travails in local dry-dock and slaughterhouse workplaces. The new home of the San Francisco Giants and eventually the 49ers was open for business with the hope that it would bring business to the area as well as sporting glory.

The greats played there, respective royalty of baseball and gridiron such as Willie Mays and Joe Montana, while The Beatles performed their last live concert together there on August 29, 1966. Candlestick Park even withstood an earthquake that measured 7.1 on the Richter scale on October 17, 1989, just before the third game of the World Series.

The initial demand for staff at Candlestick Park led to housing being built nearbyCAMERON DAVIDSON/CORBIS

One of the very junior architects working on the project was my dad, fresh out of Yale, so I have always read up on Candlestick Park and what it meant to the community. Such was the initial demand for staff at the stadium that housing was built nearby and it seemed a model enterprise.

Sadly, the Candlestick light was snuffed out on August 14, 2014, closing for good. Too much wind off the bay, they said, and also too much collateral damage from the winds of change. Grander, more corporate-friendly facilities were desired. It also required more investment in an area afflicted with socio-economic problems.

It seemed a key point, ensuring a stadium is embedded in its community, helping those around, which is, of course, easier for an English football fan to say with so many grounds central to a town or city’s geography as well as emotions. A stadium is not only for 90 minutes. It’s for every day. It’s for the community.

When new sporting cathedrals throw open their portals, such as the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, the new Lane, did for a test event on Sunday, fans’ focus is understandably internal, on the atmosphere, the facilities, the rake of the seats, and the cost and speed of service at concessions.

The half-hour rendition of “we’ve got Alli” by Spurs supporters in the 65 metre-long Goal Line Bar, and the bottoms-up beer system, caused more fascination than the impact on the surrounding area. Many of the glowing reviews concentrated exclusively on the inside. The lasting, life-changing effects of Spurs’ magnificent new home will also be felt on the outside. The building of a football stadium is not an exercise that occurs in a bubble.

Spurs fans who live nearby inevitably can see the impact but it is too readily overlooked by others, especially by followers of other clubs too busy sniping, although that might be sheer jealousy as well as textbook tribalism. It is in the nature of many football fans that nobody can have a better stadium than theirs, even when it is patently overtaken by an arena drawing on lessons learnt from theirs and other grounds, and that theirs is by far the greatest team the world has ever seen, even when struggling for form.

The blinkers need removing when Spurs’ new home is assessed. It should be a source of pride, however grudging, for all in the game. It is a reminder of what an obsessed country we are with football that one club can spend £1 billion on the setting for a strip of a grass. It drives the Premier League even further into the besotted thoughts of broadcasters, domestic and global, and that benefits all clubs.

Eight years ago Tottenham was the scene of riots, now the club have helped to improve the areaDAN ISTITENE/GETTY IMAGES

Tottenham’s new stadium throws down the gauntlet from a great height to other elite clubs considering stadium developments, such as Chelsea and Everton, showing them the quality of spec required and the paramount importance of meeting fans’ desires for optimum decibel level. The single-tier home-end stand accommodates 17,500 fans, the lungs of the new Lane as well as the heartbeat. Evertonians have already been tweeting their architects regarding their own Bramley-Moore Dock development.

It is good for the reputation of British architecture (albeit via a very international firm in Populous), provides a must-see stop on those touring London’s architectural splendours, let alone footballing fans on pilgrimages, and also transmits a timely positive message around the world.

Everyone benefits from the centrepiece of the Northumberland Development Project, and self-evidently the local community does. Four months after the riots of August 2011, starting in Tottenham and spreading across the capital and parts of the country, Chelsea fans visited White Hart Lane and loudly mentioned the damage wrought nearby, including the torching of a carpet shop and a double-decker bus. “You stupid bastards, you burnt your own town,” they sang at the locals.

But look at their town now. It is transformed. Stations such as Tottenham Hale, White Hart Lane and Northumberland Park are improved. Meridian Water station will eventually come on track. A sixth-form college, operated with Highgate School, rises up along with two developments of affordable housing. A hotel is planned. A supermarket has already popped up. “Follow the cranes,” as one club owner told me once, talking of his business ventures in up-and-coming areas. Spurs brought their own cranes and hoisted the area up.

Tottenham claim that the development will generate 3,500 new jobs and pour £293 million into the neighbouring economy every year. The club can put a price on how much the local coffers will be boosted but it is impossible to put a value on the psychological uplift. Spurs told local businesses and residents that they want to “showcase” the area, and now they have one of the most talked-about stadia in the world on Tottenham High Road. That spreads confidence and pride.

It is such a cosmopolitan area that when Spurs sent out their plans to local residents and businesses, they made them available in Albanian, Arabic, French, Gujarati, Greek, Kurdish, Portuguese, Romanian, Somali and Turkish as well as English. It is an area of great diversity and even though some small businesses have protested, the community clearly gains overall. Just as a young Raheem Sterling looked at Wembley Stadium being rebuilt and dreamt of playing there, so local children in Tottenham will be inspired by this amazing arena on their doorstep. It sends a message that sport matters, that their area matters.

To appreciate fully the significance of Tottenham’s gleaming palace and enriched hinterland one needs only contemplate the devastation on the community had Spurs moved with the loss of employment and esteem. To suggest it would have become a ghost town is too far, as a strong community heart beats there, but the redevelopment has been an opportunity of a lifetime, a catalyst for change, and the benefits are already manifest. The new Lane has really put Tottenham the area on the map. It’s a destination venue with a world-famous structure in its midst.

A Spurs fan takes a selfie at the new stadium, but its impact will be measured away from footballLAURENCE GRIFFITHS/GETTY IMAGES

Some Woolwich fans carp about the lateness of delivery of their north London neighbours’ handsome project, the increased cost, and the suggestion of similarities with the Emirates. This is the usual inter-club jousting, Derby-day duelling over steel and mortar rather than loose balls.

Woolwich’s own move in 2006, over the road from Highbury, into what is now the Emirates, has revitalised the area. Walk west from the ground, over the Holloway Road, and admire the new developments. The Emirates is a beacon spreading light and belief in the community.

There will always be the issue that facilities within a new ground are so good that fans hurry there early and stay late, and this will clearly occur at Spurs’ new home with the instantly popular Market Place behind the South Stand. This should also ease congestion and strain on local transport hubs pre and post-match, as well as generate more income for the club.

But will it harm local trade? To the layman’s eye, the experience of Woolwich shows that Piebury Corner is booming, new restaurants are opening and local pubs are still rammed on match day. Plus the number of people visiting on non-match days whether heading into the famous Woolwich museum or attending functions has soared.

All of football should admire these buildings, at the heart of their communities, bringing employment and sprinkling stardust on them, lending even more glamour to the English landscape and game.

In general a good piece BUT.........FOOTBALL | HENRY WINTER

march 26 2019, 12:01am, the times

Tottenham Hotspur’s new stadium should be a source of pride for all of football

henry winter, chief football writer

The fabled American sporting arena, Candlestick Park, opened on April 12, 1960 in the Bayview-Hunters Point district of San Francisco, a community needing love and investment after travails in local dry-dock and slaughterhouse workplaces. The new home of the San Francisco Giants and eventually the 49ers was open for business with the hope that it would bring business to the area as well as sporting glory.

The greats played there, respective royalty of baseball and gridiron such as Willie Mays and Joe Montana, while The Beatles performed their last live concert together there on August 29, 1966. Candlestick Park even withstood an earthquake that measured 7.1 on the Richter scale on October 17, 1989, just before the third game of the World Series.

The initial demand for staff at Candlestick Park led to housing being built nearbyCAMERON DAVIDSON/CORBIS

One of the very junior architects working on the project was my dad, fresh out of Yale, so I have always read up on Candlestick Park and what it meant to the community. Such was the initial demand for staff at the stadium that housing was built nearby and it seemed a model enterprise.

Sadly, the Candlestick light was snuffed out on August 14, 2014, closing for good. Too much wind off the bay, they said, and also too much collateral damage from the winds of change. Grander, more corporate-friendly facilities were desired. It also required more investment in an area afflicted with socio-economic problems.

It seemed a key point, ensuring a stadium is embedded in its community, helping those around, which is, of course, easier for an English football fan to say with so many grounds central to a town or city’s geography as well as emotions. A stadium is not only for 90 minutes. It’s for every day. It’s for the community.

When new sporting cathedrals throw open their portals, such as the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, the new Lane, did for a test event on Sunday, fans’ focus is understandably internal, on the atmosphere, the facilities, the rake of the seats, and the cost and speed of service at concessions.

The half-hour rendition of “we’ve got Alli” by Spurs supporters in the 65 metre-long Goal Line Bar, and the bottoms-up beer system, caused more fascination than the impact on the surrounding area. Many of the glowing reviews concentrated exclusively on the inside. The lasting, life-changing effects of Spurs’ magnificent new home will also be felt on the outside. The building of a football stadium is not an exercise that occurs in a bubble.

Spurs fans who live nearby inevitably can see the impact but it is too readily overlooked by others, especially by followers of other clubs too busy sniping, although that might be sheer jealousy as well as textbook tribalism. It is in the nature of many football fans that nobody can have a better stadium than theirs, even when it is patently overtaken by an arena drawing on lessons learnt from theirs and other grounds, and that theirs is by far the greatest team the world has ever seen, even when struggling for form.

The blinkers need removing when Spurs’ new home is assessed. It should be a source of pride, however grudging, for all in the game. It is a reminder of what an obsessed country we are with football that one club can spend £1 billion on the setting for a strip of a grass. It drives the Premier League even further into the besotted thoughts of broadcasters, domestic and global, and that benefits all clubs.

Eight years ago Tottenham was the scene of riots, now the club have helped to improve the areaDAN ISTITENE/GETTY IMAGES

Tottenham’s new stadium throws down the gauntlet from a great height to other elite clubs considering stadium developments, such as Chelsea and Everton, showing them the quality of spec required and the paramount importance of meeting fans’ desires for optimum decibel level. The single-tier home-end stand accommodates 17,500 fans, the lungs of the new Lane as well as the heartbeat. Evertonians have already been tweeting their architects regarding their own Bramley-Moore Dock development.

It is good for the reputation of British architecture (albeit via a very international firm in Populous), provides a must-see stop on those touring London’s architectural splendours, let alone footballing fans on pilgrimages, and also transmits a timely positive message around the world.

Everyone benefits from the centrepiece of the Northumberland Development Project, and self-evidently the local community does. Four months after the riots of August 2011, starting in Tottenham and spreading across the capital and parts of the country, Chelsea fans visited White Hart Lane and loudly mentioned the damage wrought nearby, including the torching of a carpet shop and a double-decker bus. “You stupid bastards, you burnt your own town,” they sang at the locals.

But look at their town now. It is transformed. Stations such as Tottenham Hale, White Hart Lane and Northumberland Park are improved. Meridian Water station will eventually come on track. A sixth-form college, operated with Highgate School, rises up along with two developments of affordable housing. A hotel is planned. A supermarket has already popped up. “Follow the cranes,” as one club owner told me once, talking of his business ventures in up-and-coming areas. Spurs brought their own cranes and hoisted the area up.

Tottenham claim that the development will generate 3,500 new jobs and pour £293 million into the neighbouring economy every year. The club can put a price on how much the local coffers will be boosted but it is impossible to put a value on the psychological uplift. Spurs told local businesses and residents that they want to “showcase” the area, and now they have one of the most talked-about stadia in the world on Tottenham High Road. That spreads confidence and pride.

It is such a cosmopolitan area that when Spurs sent out their plans to local residents and businesses, they made them available in Albanian, Arabic, French, Gujarati, Greek, Kurdish, Portuguese, Romanian, Somali and Turkish as well as English. It is an area of great diversity and even though some small businesses have protested, the community clearly gains overall. Just as a young Raheem Sterling looked at Wembley Stadium being rebuilt and dreamt of playing there, so local children in Tottenham will be inspired by this amazing arena on their doorstep. It sends a message that sport matters, that their area matters.

To appreciate fully the significance of Tottenham’s gleaming palace and enriched hinterland one needs only contemplate the devastation on the community had Spurs moved with the loss of employment and esteem. To suggest it would have become a ghost town is too far, as a strong community heart beats there, but the redevelopment has been an opportunity of a lifetime, a catalyst for change, and the benefits are already manifest. The new Lane has really put Tottenham the area on the map. It’s a destination venue with a world-famous structure in its midst.

A Spurs fan takes a selfie at the new stadium, but its impact will be measured away from footballLAURENCE GRIFFITHS/GETTY IMAGES

Some Woolwich fans carp about the lateness of delivery of their north London neighbours’ handsome project, the increased cost, and the suggestion of similarities with the Emirates. This is the usual inter-club jousting, Derby-day duelling over steel and mortar rather than loose balls.

Woolwich’s own move in 2006, over the road from Highbury, into what is now the Emirates, has revitalised the area. Walk west from the ground, over the Holloway Road, and admire the new developments. The Emirates is a beacon spreading light and belief in the community.

There will always be the issue that facilities within a new ground are so good that fans hurry there early and stay late, and this will clearly occur at Spurs’ new home with the instantly popular Market Place behind the South Stand. This should also ease congestion and strain on local transport hubs pre and post-match, as well as generate more income for the club.

But will it harm local trade? To the layman’s eye, the experience of Woolwich shows that Piebury Corner is booming, new restaurants are opening and local pubs are still rammed on match day. Plus the number of people visiting on non-match days whether heading into the famous Woolwich museum or attending functions has soared.

All of football should admire these buildings, at the heart of their communities, bringing employment and sprinkling stardust on them, lending even more glamour to the English landscape and game.

I've not been yet and its great to see all these touches. All the attention to detail.

When did Dumbledore get a corporate seat? (3rd row)

Or for Townsend during our opening match when he unleashes his inner Bale :townhmm:Hopefully there are those "Beware of Flying Footballs" signs in the top tier too in case Sissoko takes a shot.

Or for Townsend during our opening match when he unleashes his inner Bale :townhmm:

Klinsmann playing for inter?